![Portrait d’Alphonse de Lamartine [Alphonse de Lamartine’s portrait] by Henri Decaisne](https://chateaudelamartine.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Portrait-Alphonse-de-Lamartine-par-Henri-Decaisne.jpg)

Alphonse de Lamartine

Born in Mâcon in 1790, he became one of the major figures of the Romantic movement in France after the publication of his Méditations poétiques [Poetical Mediations] in 1820. Alphonse de la Martine was also one of the strong-willed leaders of the 1848 revolution.

Politically involved in favour of the abolition of slavery and the death penalty, as well as defender of the freedom of the press, he became the Minister for Foreign Affairs of the temporary government of 1848. He was defeated a few months later in the presidential election by Louis Napoléon Bonaparte. Together with the coup d’état of 1851, this ended his political career.

Alphonse de Lamartine passed away in Paris in 1869.

Younger Days in Saône-et-Loire

Alphonse Marie Louis de Pratz de Lamartine was a French writer and politician born in Mâcon on the 21st of October 1790.

The eldest and only male child amongst six siblings, he spent a happy, comfortable childhood in Milly. He went to the Jesuits’ school in Belley in the Ain country. As a young, undisciplined and daydreaming aristocrat, often suffering from boredom, he first aspired to a diplomatic career, yet as he belonged to a royalist family, he refused to accede to political functions under the reign of Napoleon the 1st.

He settled at his parents’ house in Milly and staved off boredom hiking for hours across the Saône-et-Loire countryside, in the vicinity of Milly and Saint-Point. He would later describe these landscapes he cherished at full length in his verses.

![julie-charles Portrait de Julie Charles [Portrait of Julie Charles]](https://chateaudelamartine.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/julie-charles.jpg)

Portrait de Julie Charles [Portrait of Julie Charles]

1811-1820: a career with long early years

Young Lamartine’s idleness was conducive to his writing process and, while still in his twenties, the young man was certain of the poetic vocation that was already brewing from his schoolboy years in Belley.

He travelled through Italy from 1811 to 1812 and while in Napoli, he met and fell in love with a girl named Antoniella who worked at the tobacco farm run by his mother’s cousin. He would write about this experience in Graziella. This trip would in fact have a crucial impact upon the rest of his life.

After the fall of Napoleon, the return of Louis XVIII gave him new opportunities. In 1815, he briefly joined the Maison du Roi bodyguard corps but quickly resigned from this boring activity before migrating to Switzerland during the Hundred Days War.

While in cure at Aix-les-Bains in 1816, he met Julie Charles, wife of the illustrious physician and lifelong secretary of the Académie des sciences. She would become his muse. They had a brief romance but Julie died brutally of tuberculosis when she was supposed to go join Alphonse at the Lac Bourget. This tragic passion would inspire him to write, amongst other poems, L’isolement [Solitude], with this famous line: “Un seul être vous manque et tout est dépeuplé” [You miss one person and the whole world seems empty].

1820, the triumph of the Méditations poétiques and the birth of Romanticism

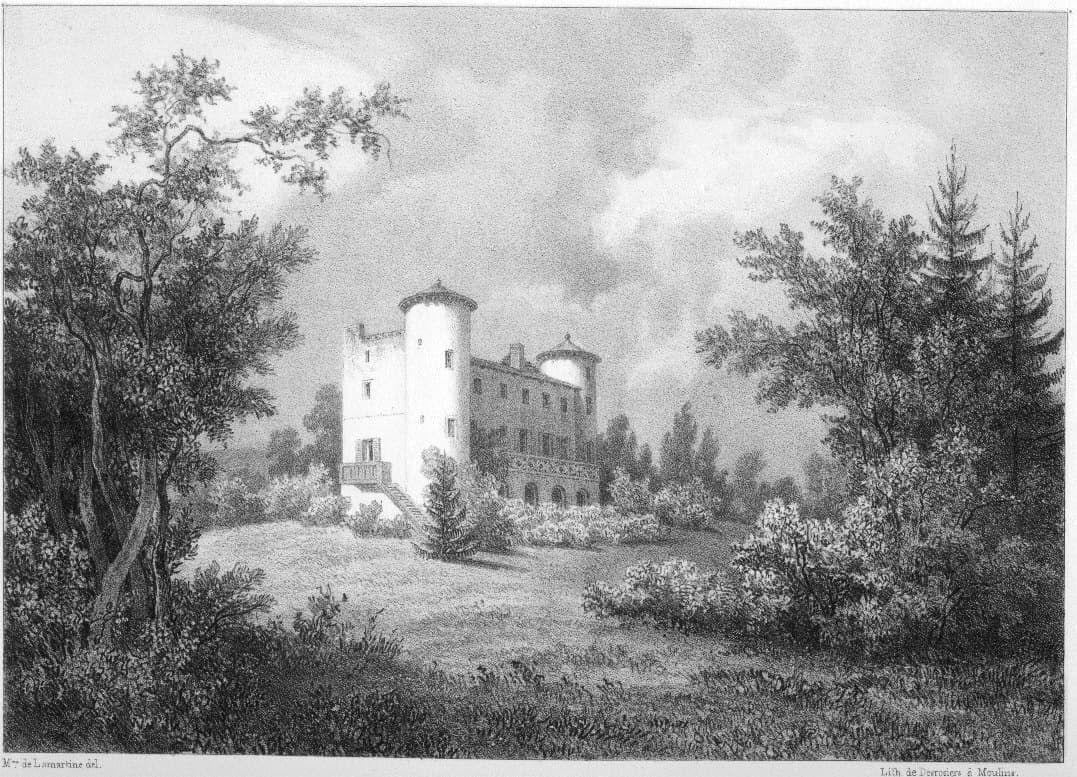

In 1820, he married Mary-Ann Birch, the daughter of a wealthy English major, relative of the Churchill’s. His father Pierre de Lamartine, gave him as a wedding gift the castle of Saint-Point which would become his family home. At the same time, his poetical success granted him access to diplomatic functions. He would spend six years in the French embassies in Italy and would not come back to France before 1826.

The Méditations are considered to bethe first literary success of the Romantic movement in France. It was, as Saint-Beuve described it later, “a revelation”. With their intense expressivity, Lamartine’s verses renewed the field of French poetry, which classical norms had rendered rigid. He moved away from classical poetry’s academic stances and gave free reign to imagination and sensibility. For the first time, a poet used the first person singular to directly express his most intimate emotions. He thus composed landscapes which reflected his qualms, and his poems dealt with themes dear to the romantic ideals: time fleeing, melancholia, depression, elation for love, the divine and the wilderness as shelters.

As a young reader of Chateaubriand, Madame de Stael, Goethe and Byron, he was predisposed to bloom amongst the romantic generation. He confirmed his vocation with the release of the Nouvelles Méditations poétiques [New Poetical Meditations] (1823), La Mort de Socrate [The Death of Socrates] (1823) and the Harmonies poétiques et religieuses [Poetic and Religious Harmonies] (1830). In 1830, at age 40, he was chosen to sit at the Académie française.

Political commitment to a republican ideal

In the year 1830, Alphone de Lamartine left his diplomatic function, which didn’t earn him the success he expected, and went on to dedicate his life to politics.

He believed his political involvement to be a necessity and wrote accordingly in the Ode à Némésis « Honte à qui peut chanter tandis que Rome brûle ! » [Shame to whom can sing while Rome is burning].

In 1831, he released a political brochure Sur la politique rationnelle [On Rationality in Politics] in which he exposed his political principles. His ideas were ground-breaking for their times: defence of the freedom of the press, freedom of teaching without any expenses, separation of the Church and the State, universal suffrage, abolition of the death penalty for political reasons and of slavery…

In 1832, he was defeated in the legislative election and left for a lengthy trip in the Middle East. In Beirut, he suffered the loss of his daughter Julia, who died at age ten from tuberculosis.

On his way back in 1833, he found out he had gotten elected representative of Bergues. He would then successively become representative of Bergues, Macon and of the Loiret.

In December of 1834, he became one of the founding members of the French Society for the abolition of Slavery. He carried on with his writing endeavour and published Jocelyn in 1836 and La Chute d’un Ange [The Fall of an Angel] in 1838.

The 1848 Politician

Starting in 1840, he stopped writing poetry to dedicate himself fully to politics. The publication of the Histoire des Girondins [History of the Girondists] in 1847 proved his commitment. He had by then become an eloquent speaker of the assembly and a formidable opponent to Louis-Philippe’s monarchy. Immersed in the liberal thoughts of his times and sensible to the fate of the proletarian class engendered by the industrial society, Lamartine, who was a legitimist back in 1820, gradually changed and eventually joined the Republicans even before the 1848 revolution.

After the fall of Louis-Philippe and during the proclamation of the Second Republic, he took part in the provisional government committee and becomes secretary for Foreign Affairs from February to May 1848. Though the government was officially presided by Dupont de l’Eure, Lamartine was its strongest man.

The 25th of February 1848, on the stairs leading to the Hotel de Ville, he stopped the rioters and had the red flag rejected in favour of the tricolour flag, which from then on would never be contested again as a national symbol.

“The tricolour flag has been seen all around the world along with the Republic and the Empire, with your liberties and your glories […] the red flag has only been seen around the Champ de Mars dragged around in puddle of people’s blood”, he declared.

The first governmental measures directly emerged from ideas defended by Lamartine in the previous years: the right to work, abolition of the death penalty, freedom of the press and reunion, direct universal suffrage for man, and the abolition of slavery, whose decree was signed on the 27th of April 1848.

A few weeks later, the “journées de juin” [the June days] unravelled his prestige. In December, for the presidential election, the French people only granted him 0.23 % of the suffrage and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was triumphally elected with 74 % of the votes.

Not too long after this failure, Lamartine withdrew himself from the political arena, with a feeling of bitterness.

1848-1869: “The literary hard labour”

During the final part of his life, he had to face worrying financial issues. Despite his considerable wealth, Alphone de Lamartine was not a very good manager and was thus forced to keep writing more and more in order to pay off his debts. His financial difficulties were made even worse by the large annuities that he felt obliged to transfer to his sisters to compensate for the properties he personally inherited.

Pressured into a “literary hard labour” according to his own terms, he continually wrote and taught, starting from 1856, a Cours familier de littérature [domestic course of literature] to subscribers, thus creating one of the first system of literary subscriptions.

Largely exhausted, he finally accepted from the city of Paris the concession of a cabin in Passy, where he passed away on the 28th of February 1869.

He is buried in Saint-Point, in accordance with his wishes.